COVID-19 Has Put Inequalities in Academia Under a Magnifying Glass

The COVID-19 crisis illuminates gendered and racialised aspects of precarity that were steeping in academia. The increased burden of unpaid care work has skewed research output. Casualised staff, many of them international, are expected to withstand the worst of the crisis. What action can we take?

COVID-19 has illuminated deep-seated inequalities overlooked during 'normal' times. As we grapple with the extent and severity of the outbreak, we have been required to isolate and contemplate the imminent cessation of economic activities. The fragility of our systems has come into sharp relief, evincing that is not necessarily the virus, but the lack of regulation and protection that amplifies inequalities among us.

What is work? What is essential?

COVID-19 gave us a new grammar to talk about what we do and how it is valued: essential and non-essential work. What we now consider essential work is the kind of work that our economies have systematically devalued. Health workers have been at the forefront of the response, with many women and minority ethnic communities at the lower-tier of the distribution, working in underfunded systems without the necessary compensation and protective equipment. Many do work that is neither considered essential nor 'work'. Women's unpaid work has increased as lockdown measures disrupted childcare provision and increased other care obligations. School and daycare closures have created new forms of stress and anxieties among caregivers (predominantly women), with a sizeable social gradient in the extent to which families feel able to support their children and provide home-schooling. Within the academe, the drop in the number of papers submitted by female academics and the skewed distribution of research grants illustrate the increased burden of unpaid care work that women shoulder.

What work is valued? What is disposable?

This crisis intersects not only with gendered but racialised aspects of precarity that were steeping in academia. As the pandemic rages across diverse geographies and international students defer entry for a year, higher-education centres face operational challenges, resulting in recruitment freezes, contracts not being extended, or scrapping of research projects. Early career academics on temporary contracts—many scheduled to expire this year—are anxious about their job security. International staff members are more likely to participate in casual employment, often unable to make any long-term commitments as their residency is attached to their work status. The experiences of international and ethnic minorities often go unheard in academia as they are less likely to participate in decision-making: non-white female academics are heavily under-represented in professorial positions across the Netherlands. These elements evince that diversity in higher education has not been accompanied by a change in normativity, with tangible consequences in terms of career prospects. Academics of diverse background encounter themselves trying harder to be accommodated, doing more service work and being less protective of their research time (if any), thus hindering their chances in the labour market. One could consider this a sign of an increasingly fragmented and market-driven academia that fails to recognise differences.

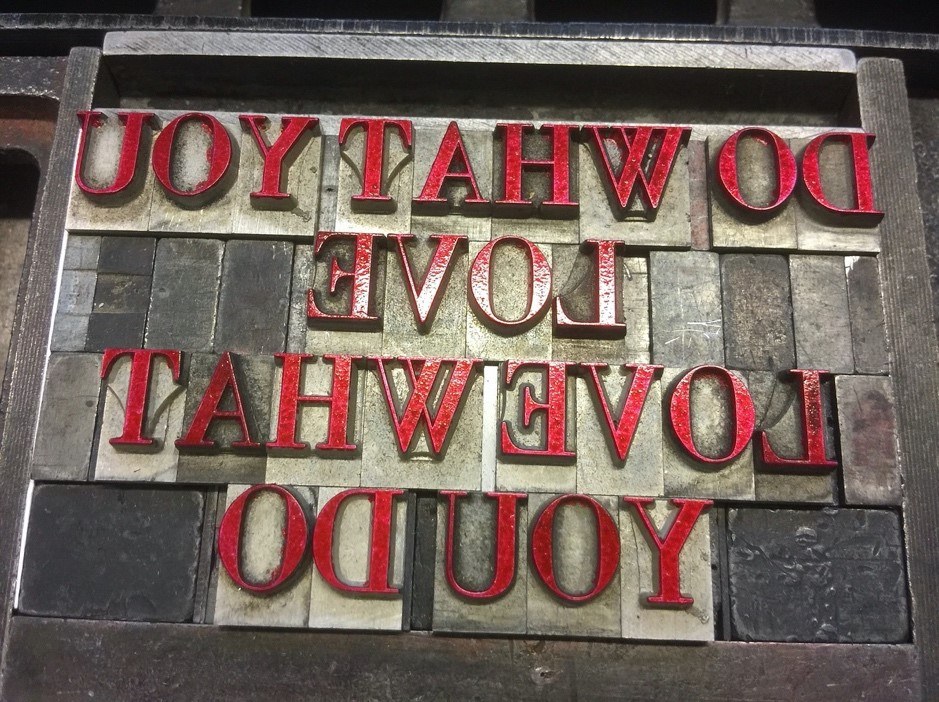

Image caption: 'do what you love, love what you do’ book print

Doing what you love is still work

Most jobs that involve 'doing what you love' make it more difficult to assert one's position and demand better conditions. It is often expected of academics to be intrinsically motivated and concerned about the wellbeing of students—and the vast majority indeed are. Yet, this expectation makes it difficult for us to demand better work conditions, particularly during a crisis like the one we face today. Support and care for students have become central to our online teaching. It is assumed that in the next academic year, most teaching will continue online, supplemented with some on-campus activities. This has initiated a university-wide discussion on how to promote a sense of belonging and support students' learning. Following a student-centred approach, faculties and programmes seems to be moving towards a system of mentoring for all first-year and master's students. A group of student mentors and tutors is expected to support our student community and ensure some form of social contact. Though this is a highly welcomed initiative, it needs to be accompanied by a reflection on how this new form of work would be valued and compensated.

A rapid response is needed

We need a post-pandemic vision of our institutional setting while we respond to the immediate challenges of online education, casualised employment, and intensified work demands. This is a crucial moment to reflect and raise awareness about how our experience in academia is affected by who we are (e.g. gender, race/ethnicity, citizenship) and the challenges to measure and capture the value we create. What can we do to take action and tackle the privileges and systemic inequalities that this pandemic has illuminated?

- Support joint actions with students and instructors. The initiative 'Stop discarding our lecturers!' and 'Stop draaideurconstructies!', led by a group of instructors at the BA International Studies, calls upon casualised staff to share their experiences with temporary and atypical contracts using the hashtags #koesterdedocent #staffshouldstay, while inviting permanent staff to show solidarity.

- Engage in discussions within your faculty and/or programme to discuss how new forms of work derived from the COVID-19 crisis, e.g. mentor programmes, will be valued and compensated. Inclusion is central to such discussions: where would this work come from? Who will be asked? How would they be compensated? Because we genuinely care for students, the conditions of and compensation for this type of work tend to become afterthoughts.

- Reach out to the LUDEN network and help us create resonance for a socially just academe. Share your different experiences, resources, challenges, and priorities through this pandemic. Help us signal the structures that allow some academics to thrive while others are left to navigate the harshness of a fragmented system.

0 Comments